Building a scrappy semantic search for my reading highlights

I’ve been exporting my reading highlights to my website for the past eight years. This has provided an opportunity to experiment with new technologies that I wouldn’t typically get to try out in my day-to-day work:

- In 2015, I built the foundation that much of the system still runs on: an email address that receives various export formats, like Kindle’s “Export Notebook to Email”, and then stores the parsed highlights in my database. These highlights are then displayed on highlights.sawyerh.com.

- In 2018, I used my reading highlights as an opportunity to experiment with natural language processing and text messaging, with the goal of making it easier to rediscover and extract insights from my highlights.

Now in 2023, Large Language Models (LLMs), like OpenAI’s GPT, are cheap and easy to use. These models are fueled by text. I have my own dataset of text in the form of reading highlights, so this seemed like a good opportunity to learn more about AI tools. There’s more to them than chatbots.

What can AI tools do for reading highlights?

Since 2018, I’ve been running my reading highlights through Google’s Natural Language Processing API and storing its output. That gave me the ability to identify entities (people, organizations, things) mentioned in a highlight, the sentiment, and a basic categorization (e.g. “Business”, “Technology”). Although I’ve had this raw data, I never put it into use — the learning curve was a bit too steep for a side project.

What I found myself wanting though were features like:

- Search across all my highlights for a topic.

- Distill many highlights down to a handful of takeaways.

New APIs from companies like OpenAI provide the building blocks to accomplish those features, in a much more approachable way.

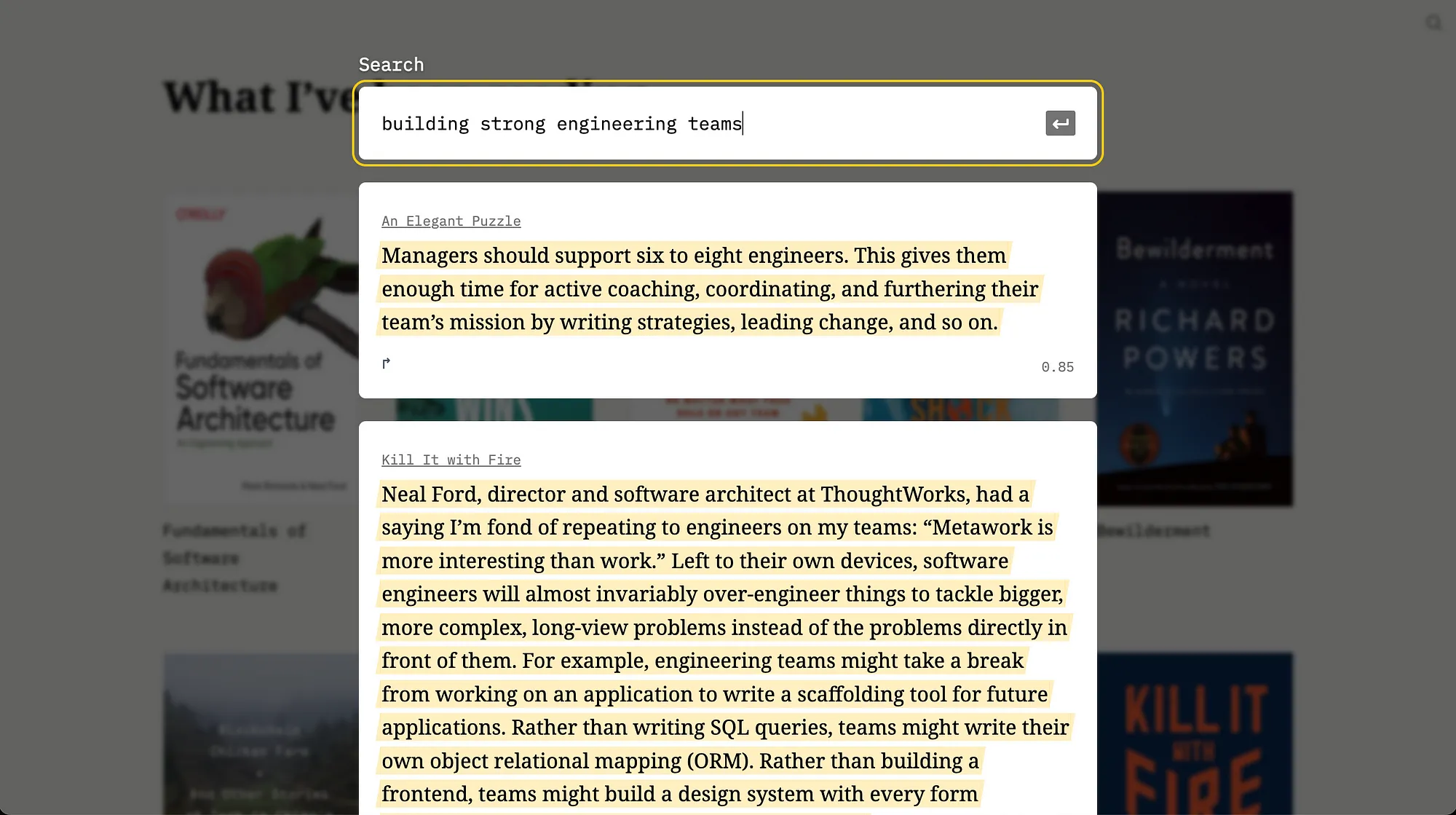

Semantic search

Semantic search is a term for the ability to find matches even when the matches don’t include the exact keywords in the search query. For example, a search query with “apple” and “banana” could include matches that just mention “grapes”.

I often find myself wanting to reference something I know I’ve highlighted before, but I can’t recall which book it was from or the exact phrasing. It would be useful to search by the topic I’m interested in and see the highlights sorted by how closely they’re related to that topic.

The main building blocks for this feature are:

- Text embeddings

- Data storage

- A pinch of math

Text embeddings

Embeddings were a concept that took a while to click for me. From OpenAI’s documentation:

Embeddings are a numerical representation of text that can be used to measure the relatedness between two pieces of text. […] Embeddings are useful for search, clustering, recommendations, anomaly detection, and classification tasks.

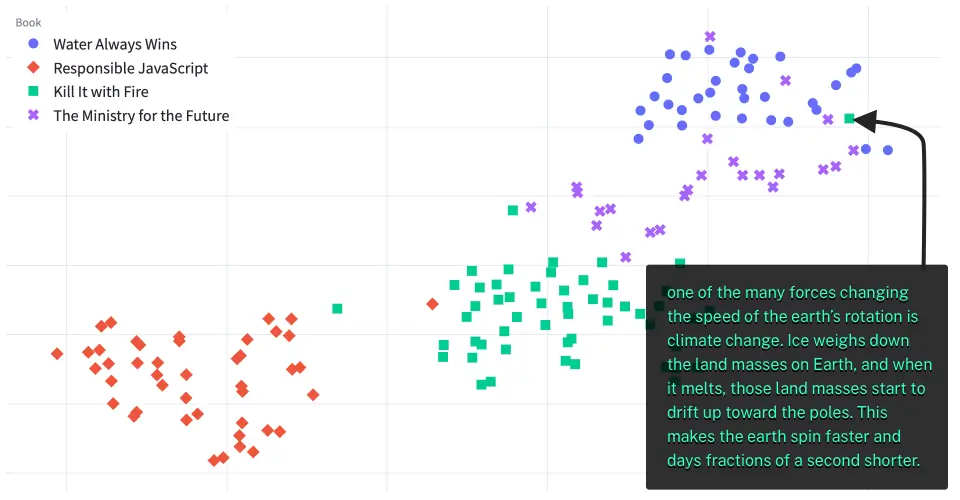

Something that helped make the concept click for me was visualizing the embeddings. Cohere has an embeddings playground that lets you add a list of sentences, and then see a visualization of the relatedness (closeness) of those sentences. For example, here’s a visualization for reading highlight embeddings from four books:

Highlight embeddings clustered by similarity

Highlight embeddings clustered by similarity

There are clear groupings of highlights from each book, but interestingly one of the highlights from Kill It with Fire — a book about legacy technology — is grouped with the highlights from Water Always Wins — a book about water management and climate change. If we look at the highlight, we can see it’s about climate change — it’s more related to the highlights from Water Always Wins.

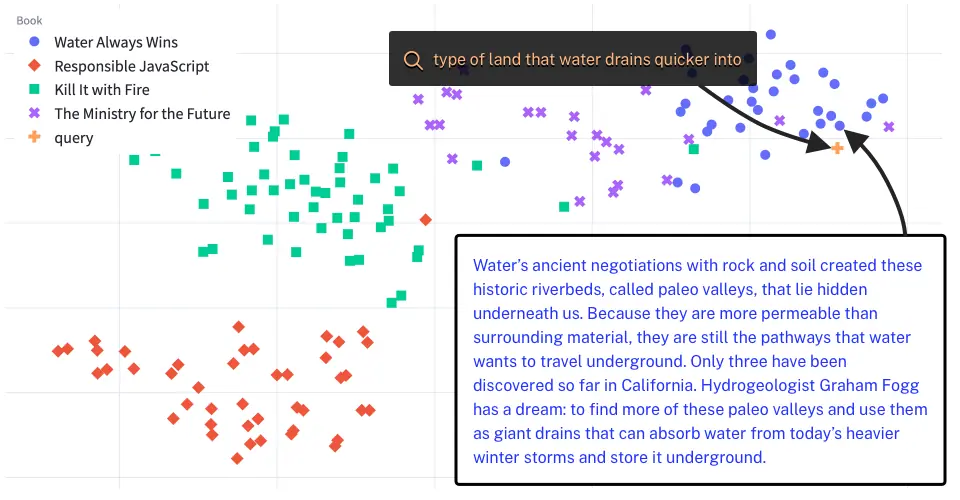

Semantic search can be built upon embeddings. A search query is just another sentence that you can create an embedding of. Once you have the query’s embedding, you can compare it against all other embeddings and return those that are closest. For example, in Water Always Wins, I learned about paleo valleys, but I have trouble remembering the term. I remember the concept — land that water drains quicker into. If I search for that concept, the query embedding gets me close enough to other highlights about paleo valleys, helping me find the highlights I was looking for:

A search query embedding clustered with highlights that are most similar

A search query embedding clustered with highlights that are most similar

Embeddings APIs

There are several companies offering APIs for generating embeddings. I considered Google Cloud’s Vertex AI service, OpenAI, and Cohere. I ultimately picked OpenAI. The two biggest factors for me were cost and ease of use.

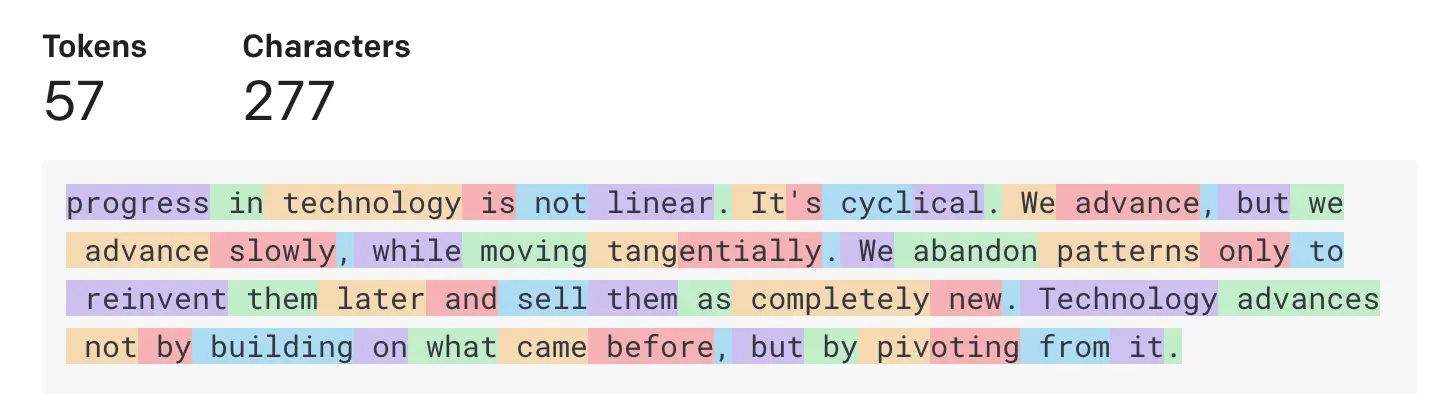

Pricing is based on the number of “tokens” in the text. According to OpenAI, “one token generally corresponds to ~4 characters of text.” You can use OpenAI’s Tokenizer tool to calculate and visualize how a piece of text is broken down into tokens.

Tokenization of a reading highlight

Tokenization of a reading highlight

I was initially worried that the costs for generating and storing embeddings for all of my reading highlights would be higher than I’d be willing to pay, so the first thing I did was estimate the costs. To do that, I needed to:

- Get the text of all my reading highlights.

- Estimate the number of tokens for each highlight. I used tiktoken, a Python library from OpenAI.

- Estimate the cost based on the total number of tokens across all the highlights

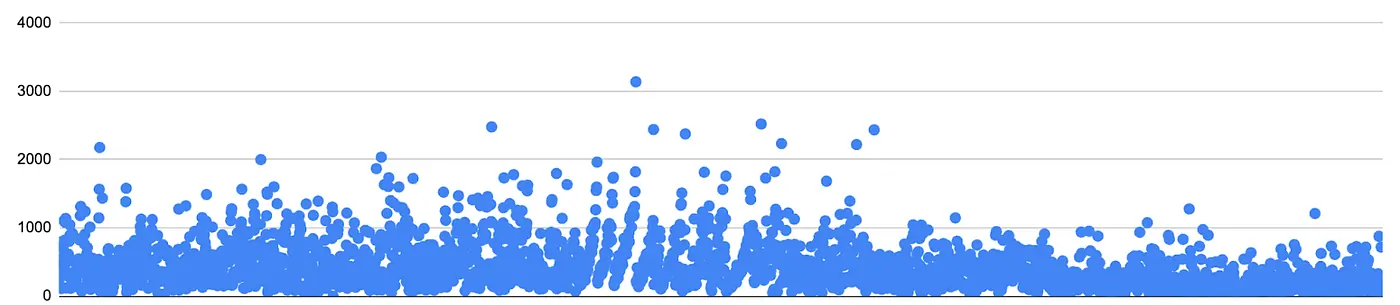

Character lengths of each reading highlight

Character lengths of each reading highlight

Turns out it’s cheap as hell. Here were the numbers:

- I had exactly 3,000 highlights. I thought for sure there was a bug in my query, like a default LIMIT, but I confirmed this was an accurate total. The largest highlight was under 4k characters.

- Tiktoken estimated the existing highlights would be a total of ~249,000 tokens.

- Using OpenAI’s pricing of $0.0001 per 1K tokens, the estimated cost for creating text embeddings for all my highlights: $0.02.

Embeddings storage

Now that I knew I could afford to create the embeddings, my next step was to determine how to store them.

A common storage solution mentioned in anything I’d read about embeddings was vector databases. These are a type of database designed specifically for handling embeddings data. Popular companies in this space are Pinecone and Chroma, but you can also utilize Postgres.

I initially experimented with using Chroma, which is open-source. I had a positive experience working with it locally on my machine. You can use it entirely offline to create, store, and query embeddings. It’s really neat and was a helpful way to rapidly prototype.

A question I had coming into this experiment was whether I could create a serverless semantic search. I don’t plan to use the feature every day, so having something running 24/7 isn’t ideal from a cost standpoint.

Chroma runs in memory, so I briefly explored whether I could run it in AWS Lambda. I ran into a few pain points related to deployment size and timeouts, so ended up scrapping that idea. In hindsight, it’s possible the challenges I ran into were instead due to my attempt to use AWS Chalice as the serverless framework, so I may revisit this idea in the future.

Turns out I don’t need a vector database

After pivoting away from Chroma, I decided to explore whether storing all 3000 embeddings in a single file in S3 and then reading them from a serverless function for each search request, would be a feasible option. My concerns were how large this file would be, and whether a search request would take obnoxiously long to complete.

It turns out you can go surprisingly far with just storing embeddings in a file in S3. As a JSON file with gzip compression, a file with all of the embeddings (and some metadata for each highlight) came in at 21.5 MB. After discovering the Parquet file format, I was able to get this down to around 18 MB. Reading and writing this data to S3 was simplified by using AWS SDK for pandas, formerly AWS Data Wrangler.

As for the HTTP request time, a request sent to a Lambda Function URL can take 9 seconds during a cold start, but around 3 seconds otherwise. To get the request time consistently down to the 3-second range, I built the search feature so that a “wake” request is sent to the Lambda once the search interface is opened, as a way to warm it up in anticipation of a real search request.

I’d not be happy with these request times if I was building something for a lot of users, but as a side project where the primary user is just me, I’m okay with waiting a few seconds if it means I pay $0 to have the feature.

There are some other tradeoffs to storing all embeddings in a single file. Race conditions are a big one. Unless you limit the concurrency of the writes/deletes to 1, there’s the possibility that multiple requests attempt to update the file at the same time, resulting in only a subset of the updates being saved. Again, since I’m the only user making infrequent writes/deletes and I know about this constraint, I’m cool with this tradeoff. For new highlights, they all get imported in a single request. I seldom delete a highlight.

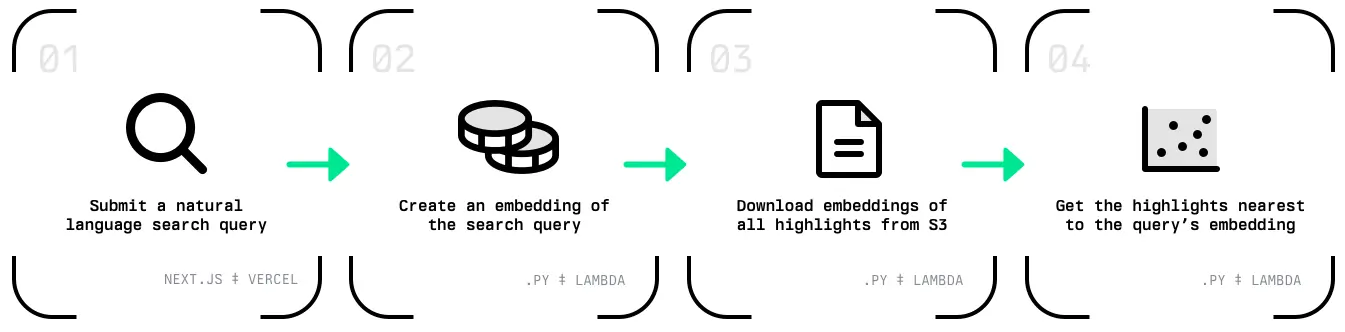

Tying it all together

At a high level, there are four main parts:

- A Lambda Function URL to send the search request to. This serverless endpoint integrates with the OpenAI embeddings API to convert the search query to an embedding.

- Embeddings of all of my reading highlights are stored in a single file in S3. The Lambda function downloads this file on each request, extremely quickly.

- The Lambda function then computes the similarity between the query and the highlights, using cosine similarity, and then responds with the top 50 similar results.

Demo of the search experience

Demo of the search experience

So far this has been working well enough for my purposes. If you’re interested in the code for this, you can check out the entire repo here, or the deployed site here.