How I export, analyze, and resurface my Kindle highlights

Update (2023): Read how I built a Semantic Search feature for my reading highlights.

In 2015, I wrote about my workflow for exporting my reading highlights, and how I publish those highlights to my personal website.

My personal challenge in 2015 and still today: How might I gather all my highlights from Kindle and put them into a personal online archive, where I can share, browse, and reflect on everything I’ve read?

At the time, the solution to this was emailing the highlights from my Kindle, parsing that email in an AWS Lambda function, saving the highlights in Siteleaf, and publishing a static site to GitHub Pages. You can read the original post if you’re interested in learning more about that workflow, but in this post, I’m going to cover my updated approach to this challenge, which is equally as over-engineered.

Three years of evolution

A secondary goal behind my original approach was to learn more about AWS and its various services. It gave me the chance to use Amazon Simple Email Service and AWS Lambda for the first time. It also gave me an opportunity to test Siteleaf’s API, a new product I was working on while I was at Oak Studios.

In the past three years, newer & shinier tools have been released and cloud services have continued to evolve. Notably, these things happened, making me consider what an update to this workflow might look like:

- Google acquired Firebase and didn’t kill it—instead adding services like realtime databases, cloud functions, file storage, and hosting.

- Google Cloud’s Natural Language service exited beta and reduced its prices.

(The only thing that hasn’t changed in the past three years is Amazon and Apple’s ebook ecosystems still leave much to desire, and Readmill is still missed every day ✊).

Extending the pipeline using Google Cloud

Observing the maturation of Google Cloud over the past three years had left me itching to find a reason to try its services. In those three years, I was also getting frustrated with certain aspects of my original workflow:

- I wanted total ownership and database-level access to my raw book and highlight data so that I could perform more advanced analysis and improvements.

- I wanted to explore ways that I might extract more information and value from the highlights, or form connections between highlights across different books.

- I wanted to automate more steps, like downloading a book’s cover and grabbing its metadata.

This seemed like the perfect project then to experiment with some of Google Cloud’s services.

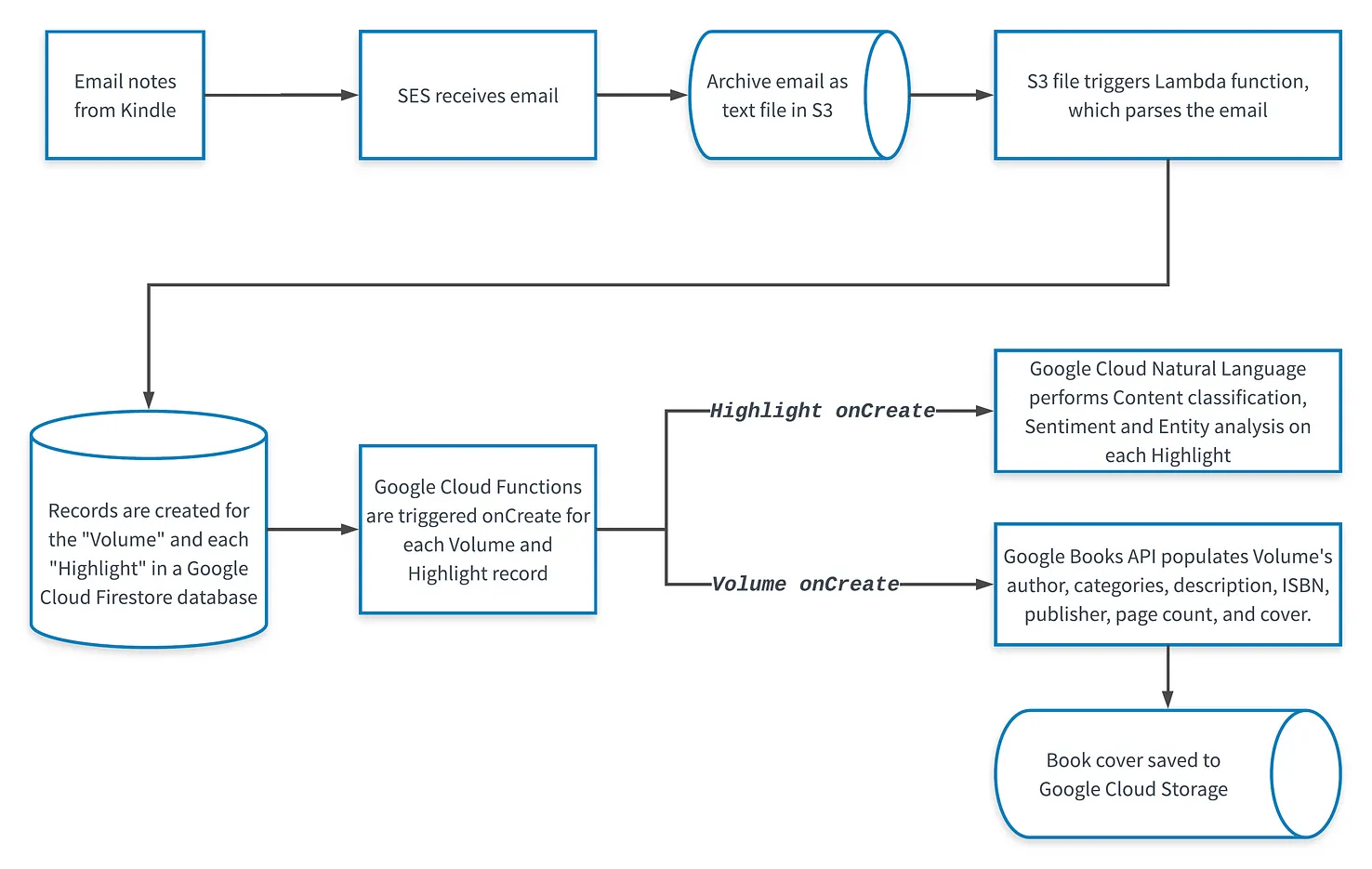

Below are some of the more interesting aspects of my updated highlights workflow. As you’ll note in the chart below, not everything has changed–I still use Amazon SES, S3, and Lambda for the first few steps. Beyond that, Google Cloud has replaced Siteleaf and GitHub Pages.

The published website is available at: highlights.sawyerh.com.

2018’s workflow for ingesting a Kindle email export. The new Google Cloud integrations are illustrated in the bottom half.

2018’s workflow for ingesting a Kindle email export. The new Google Cloud integrations are illustrated in the bottom half.

Cloud Firestore

The first step in the workflow is emailing a Kindle export to an email address connected to Amazon Simple Email Service. This email kicks off an AWS Lambda function which parses out the individual highlights and book title. Once this info is gathered, Lambda saves it in Cloud Firestore, a NoSQL document database.

Each highlight is stored as a document in a Highlights collection, and each book is stored as a document in a Volumes collection – a generic name that can encompass not just books, but also articles and audiobooks. This was the first time I’ve been responsible for managing a NoSQL database, and I still have no idea what I’m doing. Fortunately, Firebase is beginner-friendly.

Cloud Functions

One integration that I really appreciated about Firestore was its integration with Cloud Functions, which lets you automatically run backend code in response to events, without managing a server. In this case, I setup Cloud Functions to run a Node.js function each time a new Highlight or Volume is created in the database.

Natural language processing

When a new highlight is created in the database, Cloud Functions sends the highlight’s content to Google Cloud Natural Language. The Natural Language API then analyzes the text and returns:

- Named entities and their Wikipedia URLs (e.g. “New York City”)

- Categories describing the highlight (e.g. “Finance/Investing”)

- The overall sentiment (positive, negative, or neutral) expressed in the highlight

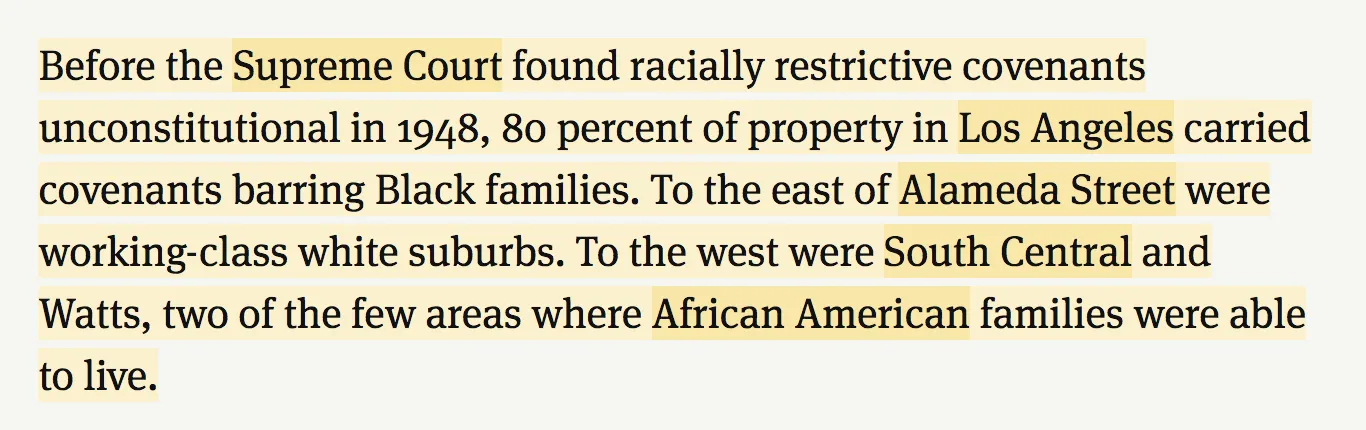

Analyzing my highlights using Google Cloud’s Natural Language service was one of the things I was most excited about. It feels like there’s a lot of opportunity in this space — combining natural language analysis with people’s reading highlights to extract insights and connections. I haven’t taken this as far as I would like to yet, but I have started to incorporate this information into the UI, emphasizing the named entities and linking out to Wikipedia. At a minimum, it makes it easier to quickly browse through my highlights to find the one mentioning the person, place, or topic I’m searching for.

A highlight from “Automating Inequality”, showing entities (e.g. Los Angeles) linking to their Wikipedia pages.

A highlight from “Automating Inequality”, showing entities (e.g. Los Angeles) linking to their Wikipedia pages.Some other ideas I’d like to explore in the future include:

- Viewing all highlights related to an entity or category. (e.g. “Show me all highlights mentioning New York City” or “Show me all highlights related to Geography)

- Sorting or filtering highlights by sentiment. (e.g. “Show me all highlights related to New York City that are positive”)

- Stealing ideas from Microcosm, a hypermedia system created in 1988, which included some innovative interaction designs for linking documents to various media.

Google Books

One of the manual steps in my original workflow was properly formatting a book’s title, subtitle, and author, as well as downloading its cover. This was one step I knew could be automated. There are a number of APIs available that could provide the information I needed, like Amazon, Google Books, iTunes, or Open Library.

Amongst other things, Google Books provides the cover, subtitle, and authors.

Amongst other things, Google Books provides the cover, subtitle, and authors.I ended up going with Google Books since it provided the best developer experience, breadth of book metadata, and high-resolution book covers. Now, I only need to create a database record with some of a volume’s title and author information, and Google Books will fill in the rest.

Overall impressions of Firebase & Google Cloud

This was the first time I used Firebase and Google Cloud. Before this, I had only ever used AWS. This initial experiment left me really impressed by their user experience and tight integrations. I found Firebases’s documentation, CLI, and JavaScript libraries to be much easier to use than AWS. Moving forward, I’ll likely default to using Firebase for personal projects.

Resurfacing highlights and remembering what I read

There’s a difference between publishing your highlights and actually remembering what you read. One of the original reasons I wanted a place to collect my highlights was because I felt it would help me better remember what I read and retain those learnings. That has definitely been true to an extent—I’m now able to remember reading about a certain topic, returning to my site to reference something, and incorporating that into my work. I’ve definitely done that with Atomic Design while I was getting buy-in for the HealthCare.gov design system, and I’m constantly referring back to Automating Inequality for stories about how automation can have unintended consequences.

But, I was mostly only remembering things that I recently read, and had a very specific use case for. Alongside the website, I’ve been trying something else: Sending myself daily SMS messages with a random highlight.

Randomized daily SMS highlights

Randomized daily SMS highlights

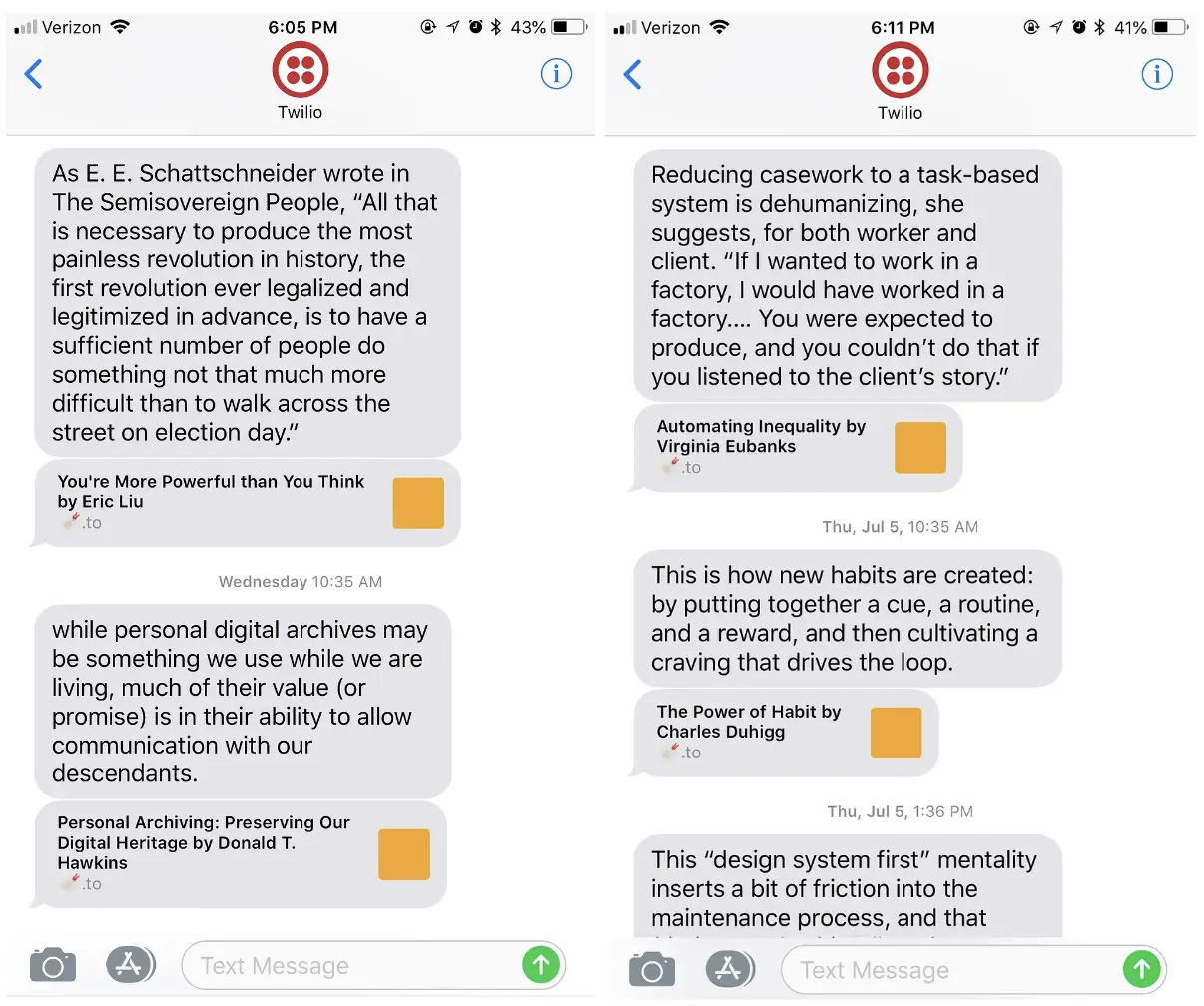

To do this, I’m using a scheduled AWS CloudWatch Event, which triggers an AWS Lambda function. The Lambda function then grabs a random highlight from the Firestore database and sends an SMS message to my phone using Twilio.

The SMS messages have been somewhat of a success at helping me retain the things I read. They’ve definitely brought my attention to highlights I’ve long forgotten, and sometimes have been uncanny in their timeliness. I’ve also found the recurring nature of seeing the same highlights has helped the information absorb deeper every time I see them.

I say somewhat of a success because, since the messages arrive three times every day, I’ve gotten used to them and generally ignore them when they come through. I’m not so disciplined that I drop everything to read the message when it arrives at 10:35am, 1:35pm, or 10:35pm. I still read most of the messages, but in batches when I have both time and interest.

Build your own

This time around, I’ve taken a more modular engineering approach in order to make it easier for others to use and potentially build their own highlights workflow. Here are the packages I’ve made publicly available (so far):

- kindle-email-to-json — An NPM package for converting a Kindle notes email export into JSON.

- highlights-email-to-json—An NPM package for converting a plain text email (conforming to the documented format) into JSON.

- aws-lambda-email-handler—The AWS Lambda function I use to parse the emails

- aws-lambda-sms—The AWS Lambda function I use for sending the daily SMS messages